![]()

Updates and Information on upcoming events from the alumni association.

MORE >>

Resuscitating Air India: Lessons to imbibe from history

K. V. Subramanian, Visiting Scholar, Indian School of Business and Assistant Professor of Finance, Emory University

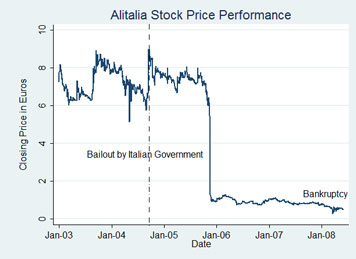

Not long ago, Alitalia was one of the largest airline companies in the world. Today it is a pale shadow of its former self, having burnt massive amounts of taxpayer money before filing for bankruptcy a year ago. The principal culprit of this debacle was the Italian government, which held over 60% in the Italian airline. By avoiding the political pain that a real (and sincere) restructuring would have caused, the government continued to pour good money after bad. The government’s subsidised financing included a bailout in September 2004. The panel below shows the precipitous decline in Alitalia’s stock price since the bailout. Back home, as our government plans a similar bailout of the ailing Air India, it would serve our policymakers, bureaucrats and the Air India management to imbibe the lessons that we can learn from the Alitalia fiasco.

Throwing money at a drug addict without reforming and rehabilitating him only enables the addict to continue his abuse and ultimately shortens his life. Similarly, providing subsidised financing to Air India without requiring it to take responsibility for a true reformation would be akin to writing the death verdict to this ailing airline. While the sound bites emanating from the prime minister’s office are along similar lines, these need to be translated into action on the ground. To be successful, this restructuring requires several elements.

To start with, let us consider the government’s bailout plan, which entails the government infusing equity into the ailing company. The bailout of Alitalia was similar. To avoid a similar outcome, I believe the bailout plan should have the following financial components: (i) the government should provide capital to Air India in the form of “convertible debt;” (ii) the lending decision on this convertible debt should be made by a syndicate comprising the government as the largest lender and a consortium of commercial banks; (iii) the consortium should bear some percentage of the last losses on the value of this debt; and (iv) existing Air India debt should be restructured in the form of a partial debt-for-equity swap.

As an investor, the government should be looking to maximise the return on its investment; after all, the taxpayers’ money that the government is pouring into Air India has a high opportunity cost since this capital could be used to fund necessary infrastructure instead. More than two decades of research by finance academics has pointed out that debt financing can enhance organisational efficiency since debt financing bonds the management of the company to make periodic interest payments. For example, academic research points out that companies that undergo leveraged buyouts successfully shed their flab, cut out wasteful expenditures and improve their operational efficiency. While the government’s plan includes a monthly review by a four-member committee of secretaries, the necessity to make periodic interest payments to the government will have the hard binding effect that monitoring cannot accomplish.

Why convertible debt instead of plain, vanilla debt? Convertible debt would provide the government the option to convert into equity. Typically, investors of convertible debt convert into equity when they expect the company’s performance to shoot north. The government could do likewise once Air India’s restructuring starts showing signs of success.

How should the parameters of the convertible debt – such as the interest rate, the time period after which the debt becomes convertible – be set? This brings me to the second component of the bailout plan. The financing must aim to minimise the risk that Air India remains passive and continues wasting resources without implementing the necessary restructuring. For example, while Eastern Airlines filed for bankruptcy in the United States in 1989, it failed to undertake the necessary restructuring and kept flying in bankruptcy until the value of its assets had been driven almost to zero. As a result, more than 18,000 employees lost their jobs and pensions. To avoid this problem, I propose that the lending decision be made by a syndicate comprised of the government as the largest lender and a consortium of commercial banks. To align the consortium’s incentives, some percentage of the last losses on the debt must be borne by the consortium. In this way, the government would ensure monitoring of Air India’s post bailout performance by both the private parties and the government.

The bank consortium would also be very useful in effecting a restructuring of the existing debt. Without such restructuring, any capital infusion by the government will only serve to fulfill the obligations of the existing debt holders. Reducing Air India’s leverage through debt-for-equity swaps will enable Air India to use the capital infusion to fund necessary investments and in the process emerge healthy after the bailout. The bank consortium would also be useful in arranging “bridge financing” that Air India needs to tide over its current liquidity woes as well as in structuring the parameters of the convertible debt issue.

Before providing Air India the financing, the Air India management needs to put forward a concrete plan including specific activities that the management has to undertake on the strategic, financial and operational fronts. On the strategic side, a critical analysis of the international and domestic routes and their profitability must be presented to the Committee of Secretaries and the bank consortium, with such analysis leading to specific entry/ exit decisions on each of the routes.

On the financial side, Air India needs to decide if it is going to undertake hedging to protect itself against oil price volatility. Since its primary business is that of an airline, its competence does not lie in taking a view on the direction of oil prices. Therefore, it makes prudent sense to hedge the risk stemming from oil price volatility.

On the marketing side, the airline needs to provide a focused brand proposition to the customer. A low-cost, no-frills airline that is reliable and punctual would be such a clear proposition. As the marketing experts tell us, one of the keys to long-term success is to set the right customer expectations, communicate them clearly, and, most importantly, to keep the customer experience consistent with expectations.

On the operational side, the management needs to be clear about the wage and manpower cuts that are necessary to trim its waistline. Finally, the government needs to provide its commitment to implementing the hard decisions. For example, the Alitalia management had requested a workforce cut of 5,000 out of the 20,700 existing workforce in September 2004. The Italian government dragged its feet on the politically sensitive decision and the resulting cut was restricted to 2,500 – half the originally slated target.

The outcome that befell Alitalia is one that Air India must avoid at all costs.